Ute language classes aimed at certifying teachers

If you open a copy of the Ute Reference Grammar book written by Tom Givon, you will come across the “First Word” written by the Ute Language Committee in August of 1979. The final paragraph reads in Ute; “’áavu-‘ura tuvuchi núu-waygya-ru-mu ka-‘ava’na-wa-tu-mu miya’ni, náagha-tu tavay-‘ura ká-miya’ni-vaa-‘wa-tu-mu. ‘úru-‘ura po‘o-kway-ku-aqh, núu-‘apagha-piu ka-ma’ayh-paa-‘wa-tu. Togho-sapa-‘ura númu po‘o-qwa-y-aqh.” This quote translates to: “There are few speakers of our language left now, and some day they will not be walking the earth anymore. This is why we must write it down, so that our language will not be lost. For this reason, we have written this book.”

In November of 2020 – over 41 years after those words were written – only 32 members of the Southern Ute Tribe were fluent speakers of the Ute language.

Nearly two years later, the progress of language reclamation is alive with the help of the Southern Ute Tribe’s Culture Department, the Southern Ute Education Department, and Fort Lewis College’s School of Education. Both tribal departments along with Fort Lewis College’s Dean of the School of Education, Dr. Jenni Trujillo; and Dr. Stacey Oberly have worked on establishing the Southwest Indigenous Language Development Institute (SILDI) in 2021 as part of the Southern Ute Tribe being awarded a language preservation grant from the Administration for Native Americans (ANA).

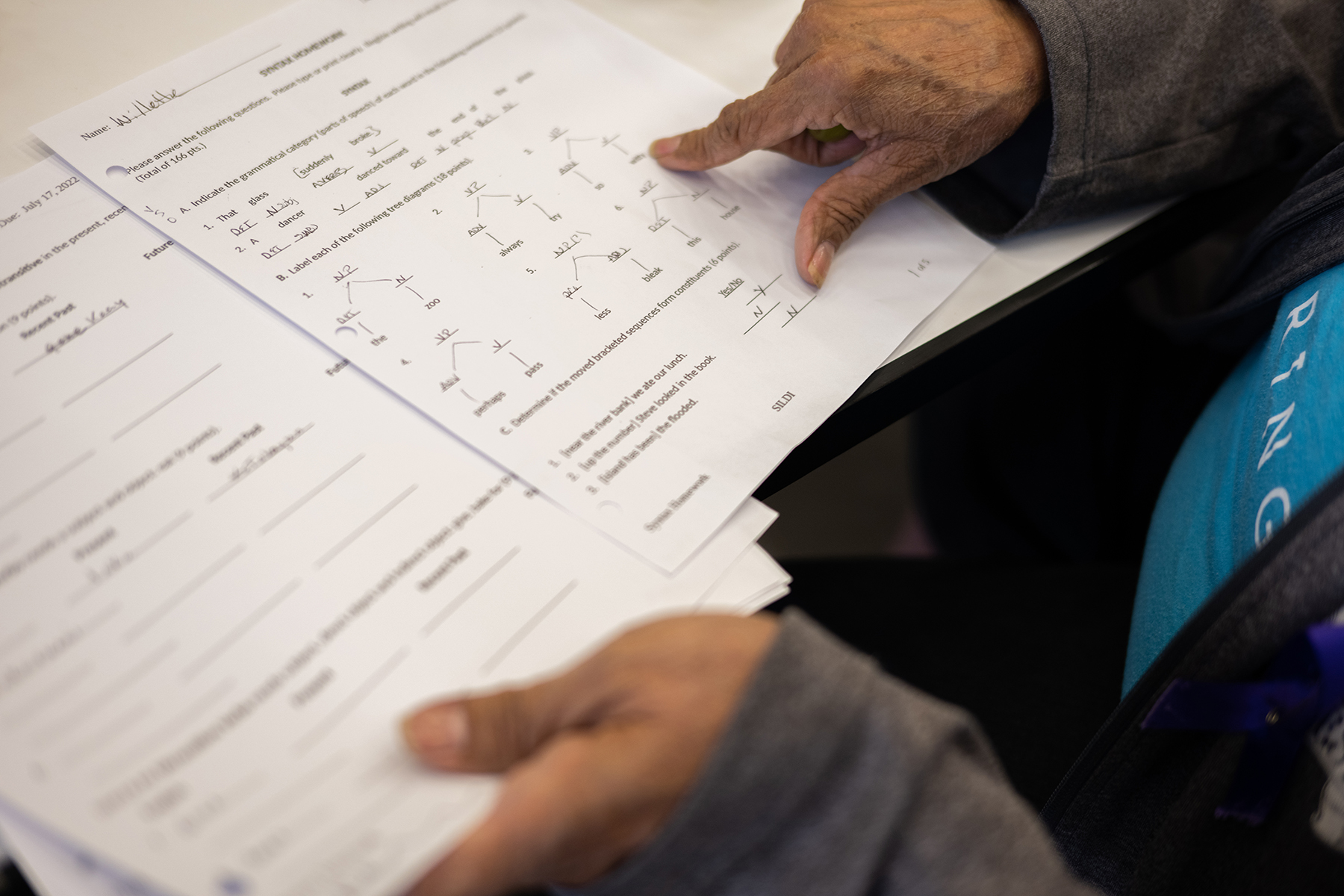

The grant is funding a 10-course program which will certify over 30 students – meeting the minimum requirement of 15 students – from across the three Ute tribes to become instructors of the Ute language through in-person and online instruction. The classes are flexible to COVID-19 restrictions and guidelines and are offered both in-person and via Zoom for students attending the classes. Seven sessions have been completed since June of 2021, with the most recent session being Ute language syntax held Monday, July 11 – Saturday, July 16, at the Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum’s large classroom. This session on syntax was instructed for the first time by Dr. Amy Fountain, a linguist from the University of Arizona.

“Southern Utes are fortunate to have a community with language,” Fountain said. Fountain’s work focuses on helping tribes across the United States reclaim their traditional language by introducing the academic theories and approaches to learning language, while also giving room to traditional forms of learning. “I can give the structure and terminology, so [the class participants and Ute tribes] can do what they need,” Fountain said.

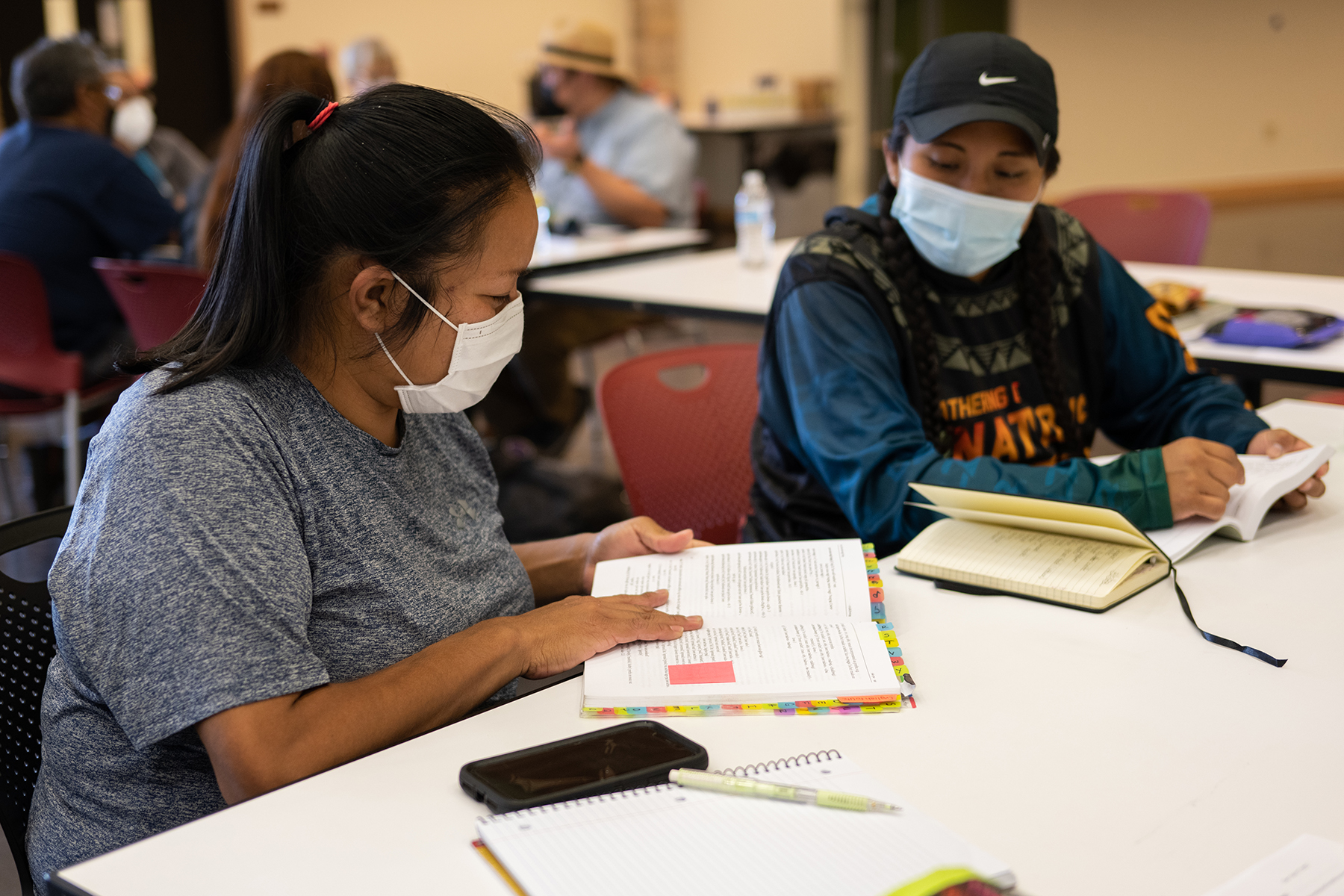

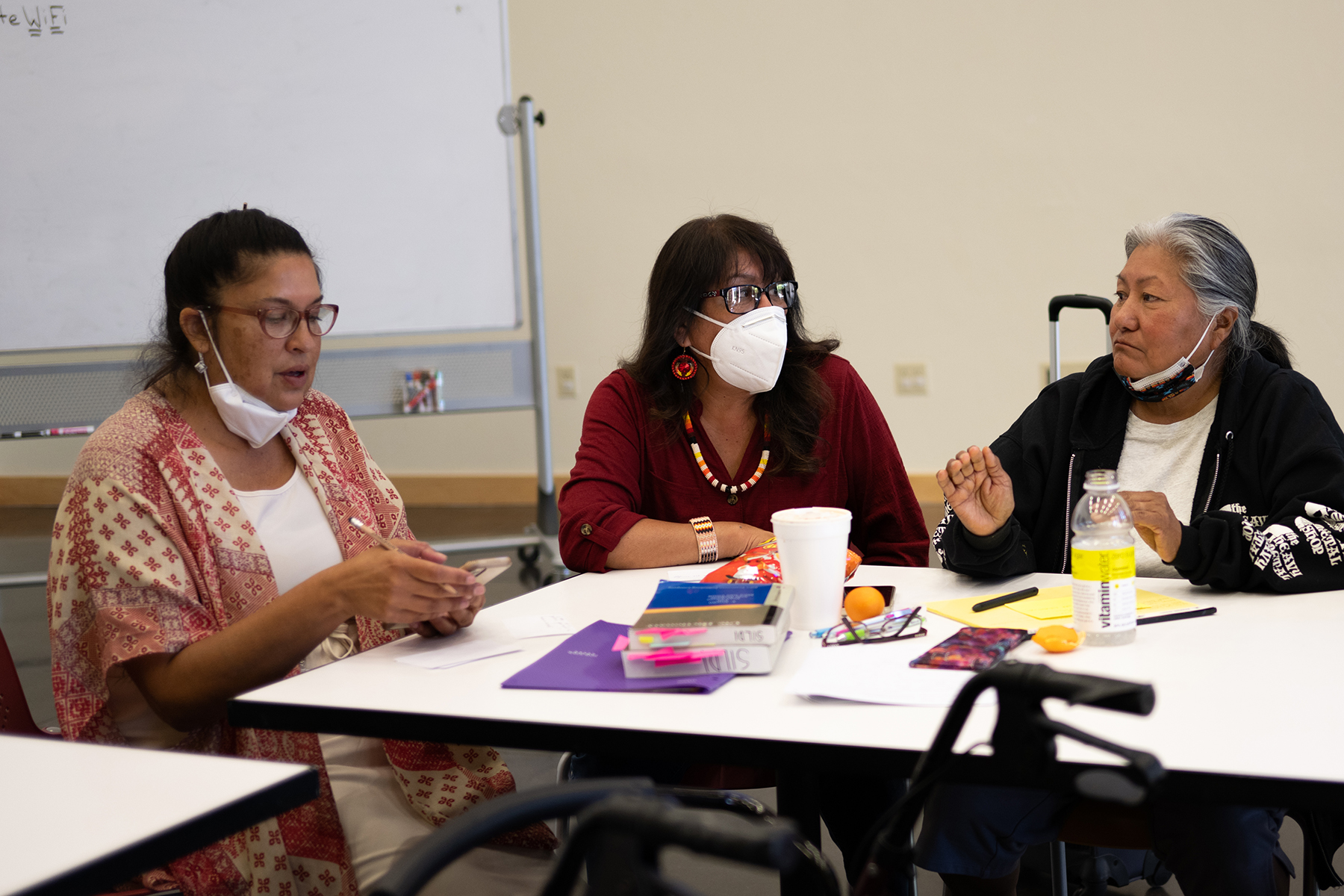

Students of the program can learn the Ute language in a fully immersive and collaborative learning space. The result is a class that features more natural learning approaches through music, traditional songs, cultural objects, creative projects, and group work that adheres to the interests of the students themselves. Elders are also encouraged to visit the classes to see the progress of students and nurture the immersion atmosphere of the program.

“It gives an opportunity for all participants to work with elders to learn and take in as much Ute in as possible,” SILDI student and Cultural Education Coordinator, Crystal Rizzo explained. Students then have a unique opportunity to ask questions of elders, who are fluent in their dialect, about the Ute language and supplement what they are learning in class. This approach helps students practice some of the more difficult aspects of Ute language, like phonetics and how the language is structured grammatically.

“I feel like our language has a sound-based system,” Tribal member and SILDI class student, Crystal Ivey explained. “It’s essential to have that sound-based system in place to learn it.” Ivey continued to explain that word association is a key foundation for first time learners of the Ute language. Syntax and how you say a sentence is just as important as phonetics and makes the difference between how it can be interpreted in a conversation.

“[Ute] has many examples of how to say things,” SILDI student and Cultural Media Technician Kree Lopez explained. “You can say something, and it has so many different meanings with Ute. There isn’t a basic one word describes everything like how English is. It can mean multiple different things just by a different sound or one word change.”

Lopez explained that Ute sentence structure is often perceived as being “backwards” to those whose first language is English, but to Ute speakers, it explains objects in a more “natural” form that makes sense. “Ute is very straightforward, to the point, and very blunt,” Lopez said. “It’s common sense sometimes.”

While the process of learning the Ute language phonetics and syntax has been a challenge for most students, older students have seen it as an opportunity to begin a healing process through language reclamation. “When speaking Ute, you get a good feeling,” Tribal elder Willette Whiteskunk said while discussing her experience within the course and past trauma from not being able to speak Ute as a child. “I am healing by allowing myself to speak the language.”

The loss of traditional indigenous languages has been a major issue for tribes in the United States as it was forbidden to teach it in residential boarding schools, where Native students were forcibly taught the English language. In many cases speaking one’s own language was even discouraged at home, furthering the effort to assimilate Native peoples to Western culture. As a result, the number of fluent speakers of Native American languages dwindled to critical levels over time. Today the loss of Indigenous language is perceivable within many tribal communities in North America.

Tribes such as the Navajo Nation have started implementing language revitalization programs for their members; going as far as introducing the Diné language on popular mainstream language apps like Duolingo for free.

The three Ute tribes have begun similar efforts of language revitalization. Ute Mountain Ute now offers a language app that is free to access on mobile app stores for the general public. The Southern Ute Tribe’s Culture Department has Ute language dictionaries and textbooks written by Tom Givon, Pearl Casias, Vida Peabody, and Mary Inez Cloud, which are free to the Southern Ute tribal membership. The largest step to language reclamation for the Southern Ute Tribe was the creation of the Southern Ute Indian Montessori Academy and its Ute language curriculum in the early 2000’s.

The SILDI program aims to continue the language preservation efforts by creating more certified teachers for the Ute language to teach the next generation of Ute speakers.

For Crystal Ivey, the SILDI classes offer hope in the language revitalization efforts of the Ute Tribes. Since moving to Hawaii, Ivey works as an elementary school teacher and helps teach the Hawaiian language as part of the state curriculum. The indigenous Hawaiian language was once believed to be extinct until the 1980’s when efforts were made to revitalize it. “It’s made me really excited to see what is possible; knowing it is possible for Ute to be alive and thriving,” Ivey said. “I’m really excited to see a large group of people come together to help revitalize the language.”

After the summer session on Ute syntax, the penultimate Ute Immersion II course will be held in the fall; the final Ute Immersion III course will be held in the Spring of 2023. After completion, students will receive full certification and be able to teach Ute within their communities.

“Language is at the root of who we are. It connects us to our ancestors. Language is what connects you to the Creator,” Crystal Rizzo said. “We have such an important opportunity with future Ute speakers to preserve the language.”