US 160 Wildlife crossing a boon for big game migrations

Real time data shows quick adaptation to underpass, overpass near Lake Capote

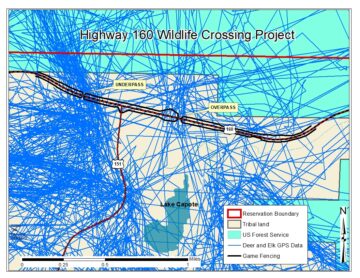

Last summer, tribal dignitaries and key personnel from the Colorado Department of Transportation, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and the Southern Ute Indian Tribe came together to celebrate the completion of the US 160 Wildlife Crossing Project neighboring Lake Capote. The project includes both an under and overpass for large game, as well as improvements to the intersection of US 160 and CO 151, which include fencing, earthen escape ramps and deer guards. This past fall marks the first migration season where animals encountered the completed project and began to readily use both the over and underpass structures in their annual migration routes.

The Southern Ute Wildlife Division installed game cameras to monitor how many animals used the structures and the results have been very encouraging. Species caught on camera include mule deer, elk, red fox, gray fox, coyote, mountain lion, cottontail rabbit, and snowshoe hare.

“There are similar structures across the western states designed to keep elk off highways, but the overpass at Lake Capote already looks to be more successful than most,” Southern Ute Wildlife Division Head, Aran Johnson said. “Elk use of the overpass has been a highlight. Images captured by Wildlife Division cameras show several large herds of elk using the overpass, which isn’t often seen at other projects.”

Some of these images were shared with other agencies so they could be assessed by a range of experts in the field. Patricia Cramer, PhD, an independent wildlife and road ecology researcher who has studied wildlife crossings across the United States was shown images of elk crossing the Lake Capote overpass.

“This video shows more elk, and more various ages and genders of elk using the overpass than any other monitoring video or series of photos have demonstrated in the continental U.S. at any structure,” Cramer emphasized.

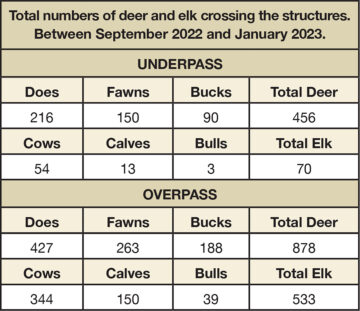

In total, between September and January the cameras recorded 1,334 mule deer and 603 elk crossing north-to-south, under or over Highway 160 at the project site. The north to south movement generally indicates animals migrating from summer range north of the highway to winter ranges on the reservation. Research of similar projects across the western United States shows that elk and deer use of these types of structures continues to increase for up to four years after completion of construction as the animals become familiar with the site and get more comfortable with crossing over or under the highway. As winter has set in and deer and elk have settled onto their winter range near the project site they are crossing back and forth daily using the structures, keeping them off the highway and keeping motorists safer.

“In the early 2000s, GPS integration into radio collars was new technology; it changed everything in terms of the data that could be gathered from collared animals, “Johnson explained. “Previously a radio collar simply transmitted a signal that a biologist followed with a receiver and tried to mark a location on a map. Best case scenario, with lots of time in airplanes, that biologist could record a dozen (not so accurate) locations for an animal in a year. This method was OK for making general assumptions about seasonal migrations; timing, survival, location of summer and winter ranges, movement corridors, but it was very labor intensive and quite expensive.”

With GPS technology, radio collars began collecting data around-the-clock at set intervals. Where a biologist collected a dozen annual locations of an animal in the past, with a GPS collar they could now get thousands of very accurate locations on that same animal over multiple years.

In 2004 the Tribe’s Wildlife Division started using GPS radio collars to track mule deer on the east side of the Southern Ute Reservation. The fact that mule deer were migrating on, and off tribal lands wasn’t surprising, past tribal biologists had demonstrated that. It was the amount of data and how it was analyzed and interpreted that was brand new to the Tribe and to state and federal partners that assisted with the work in those early years. New techniques for modelling large data sets allowed biologists to envision not just where animals were moving seasonally, but to know precisely when these events kicked off, how fast they moved across the landscape, and more importantly, what challenges they faced trying to get between seasonal ranges. The mule deer project lasted until 2010 and then the Tribe transitioned to radio collaring elk, which it has continued to do since 2013.

“One thing that immediately stood out from the early data on was where and when collared animals were crossing US Highway 160,” Johnson said. “The Colorado Department of Transportation has recognized US Highway 160 in Southwest Colorado as one of the most dangerous in the state for wildlife vehicle collisions and the radio collar data helped explain why; the San Juan mule deer and elk herds are crossing the highway enmasse twice per year on their seasonal migrations.”

“This was known anecdotally, but to map it precisely on paper with real-world data linking crossing points and high-hit areas was a new thing locally,” he said. “For deer and elk moving on and off tribal lands on the east side of the reservation, a clear pattern emerged of animals crossing the highway near Lake Capote. Dreaming began about a project to get deer, elk, and other wildlife safely across the highway way back in about 2008.”

Luckily the project idea had proponents in the tribal organization through the years including tribal planners, tribal project managers and most importantly Tribal Councils. They all recognized the dangers of wildlife vehicle collisions to divers and the impacts they have on wildlife populations. Partnerships between the Tribe, CDOT and Colorado Parks and Wildlife as well as support from the Colorado Wildlife and Transportation Alliance saw the funding pieces fall into place. Construction took two summer seasons to reach completion on the two crossing structures as well as the game fencing that is critical to guiding animals to those crossings.

The Wildlife Division will continue to monitor the project monthly. Later this year, CDOT expects to contract an independent researcher to investigate the effectiveness of each aspect of the project. The biggest indicator of the success of the project will be how much it reduces wildlife vehicle collisions in the project area. It’s expected that the new infrastructure will reduce collisions by 80-90%, which is what other similar projects have experienced across the West including similar structures located in northern Colorado.

The 11-million-dollar project was made possible primarily through CDOT funding with a 1.3-million-dollar contribution by the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, using funds available through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Additionally, Colorado Parks and Wildlife helped fund this multi-year project along with numerous NGOs including The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Mule Deer Foundation and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation.

“Considering that almost 2,000 deer and elk were kept off the highway in this first fall migration season, and many more as animals circle the project site on winter range — the results are already speaking for themselves,” Johnson said.