The U.S. Government’s agenda for American Indians, since the beginning of the reservation era, was straight forward: “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Capt. Richard H. Pratt made these sentiments known in a speech in 1892. Pratt was the founder and longtime superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, which was used as an educational model for Indian boarding schools throughout the United States.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs led the effort to indoctrinate Indigenous youth through boarding schools and day schools. Students who attended government sanctioned educational institutions, often forced by threat of legal action, were frequently subjected to physical and emotional punishment if they did not conform to American lifeways and speak English. Because of unsanitary conditions and ill-equipped medical staff, many students lost their lives to illness and or infection.

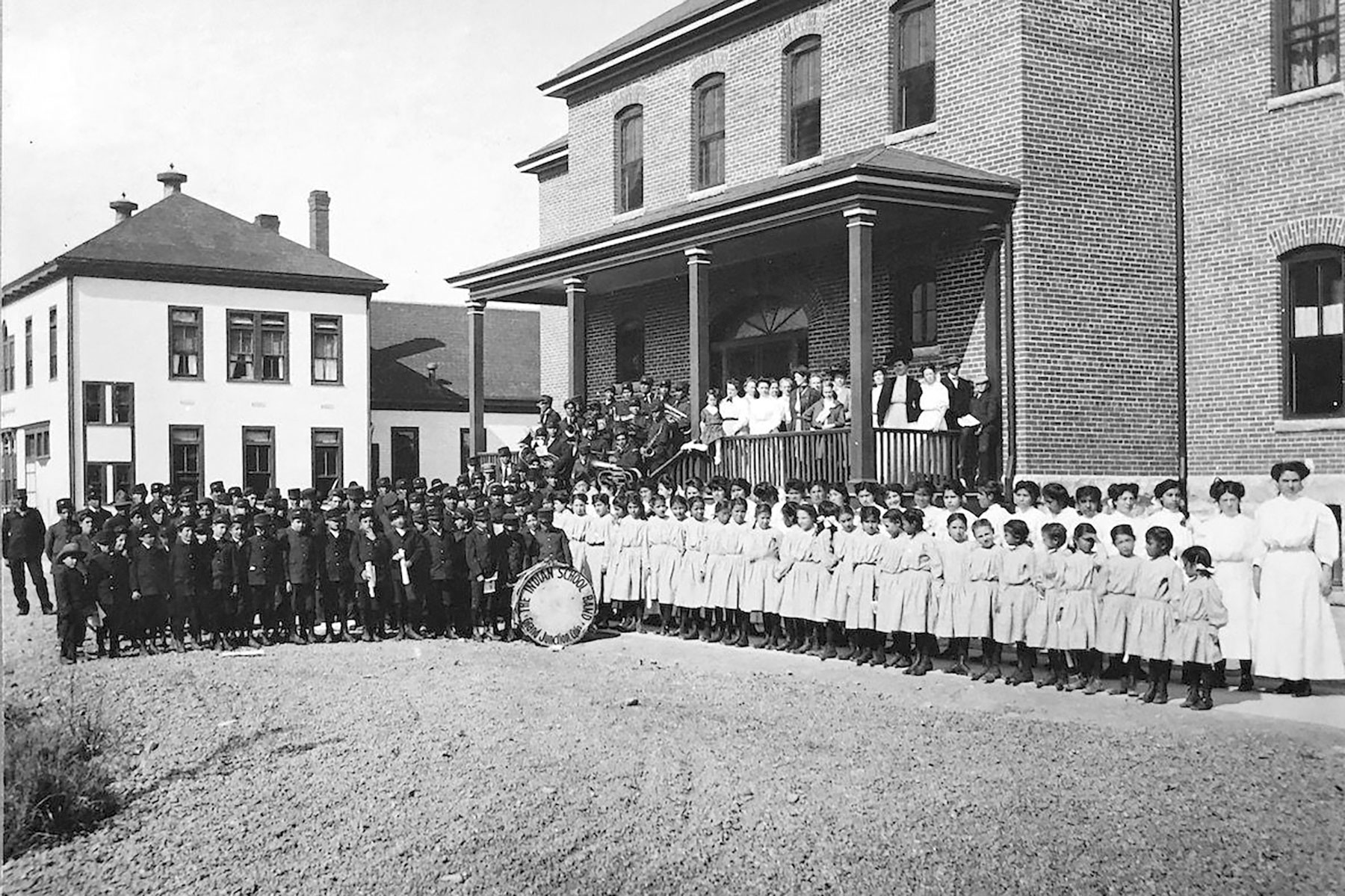

Colorado’s first off-reservation Indian boarding school was established in Grand Junction in 1886. Although the school was originally created to educate Ute youth, Southern Ute tribal members were reluctant to send their children, after twelve-students died while attending the Albuquerque Indian School in New Mexico. In operation between 1886-1911, at least twenty-three students died for various reasons while attending the Grand Junction Indian Boarding School.

Currently, there is an on-going project involving cultural preservation representatives from all three Ute sister tribes. At the moment, only a fraction of the students have been identified and culturally affiliated with descendent communities. Historic records indicate that at least one student was Ute; however, it is unclear how many, if any of the unidentified students who perished, while at Grand Junction Indian Boarding School, are Ute. By publishing this article, it is our hope that anyone with information will come forward and assist in the investigation.

Colorado History of Indian Education Among the Utes

The earliest documentation of federal involvement in the education of Utes is evidenced in the Treaty of 1868. Article 8 states that education was necessary, “to ensure the civilization of the bands entering into this treaty.” The U.S. Government established several educational programs at various Ute agencies. The first schoolhouse on the Southern Ute Indian Reservation opened in 1886 and was named the Ignacio Indian School.

The Grand Junction Indian Boarding School opened the same year as the Ignacio Indian School. Interestingly, the original intent of establishing the school in Grand Junction was to remove and educate Ute youth away from their communities. However, after unsuccessfully pursuing the Ute Indian Tribes, administrators forfeited their instructional objective and placed neighboring reservations in their crosshairs to reach their enrollment quota.

In 1889, the Grand Junction Indian Boarding School demographic was comprised of more than a dozen different Indian Nations. Dr. John Seebach, assistant professor and archaeologist at Colorado Mesa University, was quoted in the Daily Sentinel on April 9, 2018, as saying “…the student body included Navajos, Apaches, Hopis, Pimas, Papagos (now known as Tohono O’odham), Pueblo Indians, and even eight tribal members from the Upper Midwest. Only eight of them were Utes.”

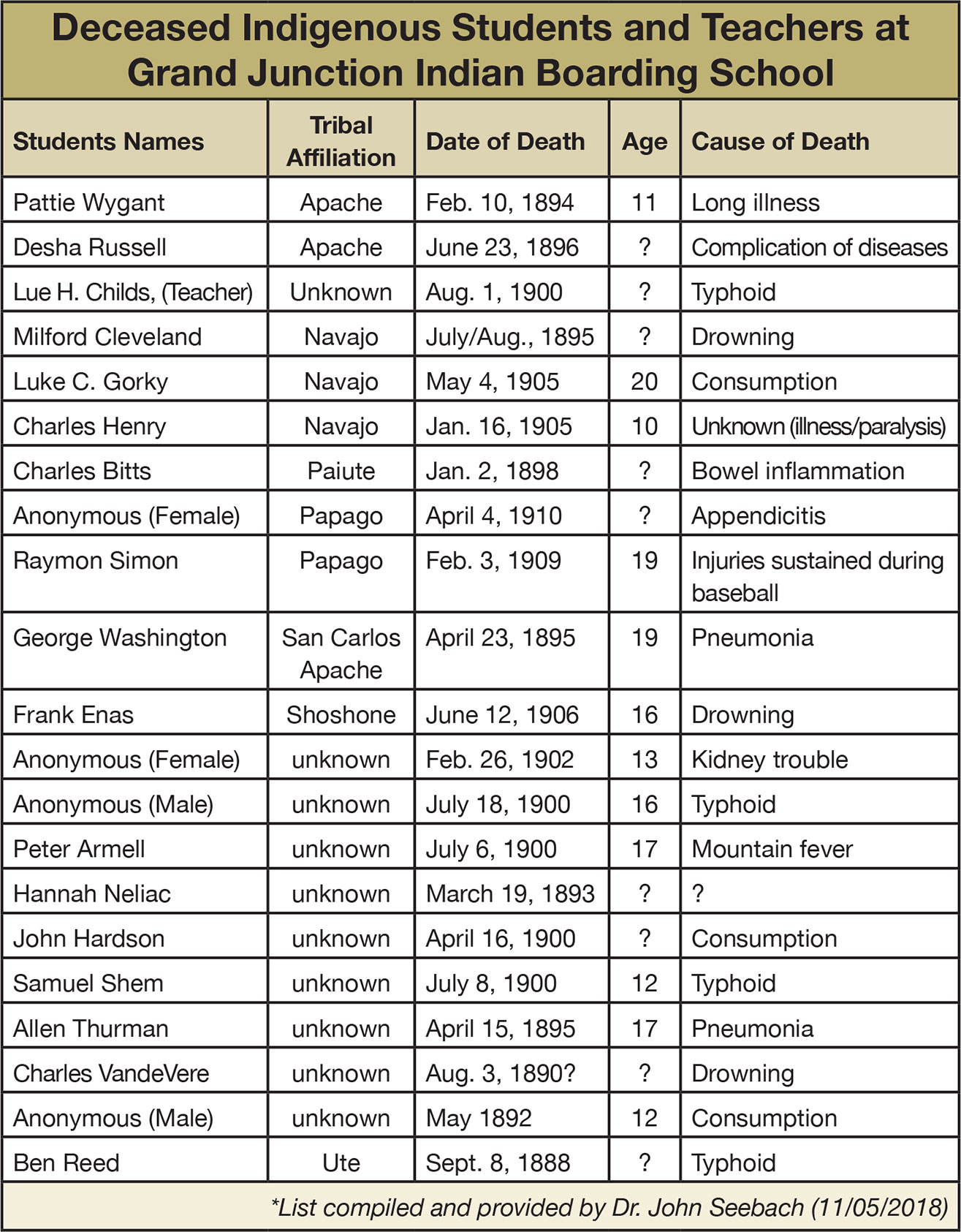

According to Dr. Seebach, at least twenty-one enrolled American Indians died while attending the school. As of November 2018, based on a list provided by Dr. Seebach, four students have not been identified by name, while eleven of the twenty-one students were associated with a tribal affiliation. The students who died were not given a proper western burial with a headstone. Therefore, paired with the lack of proper documentation, the location of the cemetery is unknown today.

After the school closed in 1911, the State of Colorado purchased the building and turned it into a home for people with disabilities. One June 10, 2016, Governor John Hickenlooper signed Senate Bill 16-178, which mandated that the Grand Junction Regional Center (formally the campus of the Grand Junction Indian Boarding School) be vacated and sold. On Jan. 9, 2018 it was confirmed that the property would be sold regardless of the graves on the premises.

Consultation with Descendent Tribal Communities

On April 4, 2018, Dr. Seebach mailed notifications and consultation requests to the three Ute tribal governments, as well as to the other tribes affiliated with the institution based on the Grand Junction Indian Boarding School’s records. Ben Reed is listed on those records as being form the Uintah Agency and died from typhoid on September 8, 1888 (Table 1). It is unknown if the other ten students with no tribal affiliation were of Ute descent.

The Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute Indian Tribes were also contacted because of the 2008 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU): The Process for Consultation, Transfer, and Reburial of Culturally Unidentified Native American Human Remains and Associated Funerary Objects, Originating from the Inadvertent Discoveries on Colorado State and Private Lands (State Process). The State Process is unique to the United States because it is the only one of its kind in existence.

The Grand Junction Indian Boarding School project is subject to the State Process instead of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act due to its land status. The state of Colorado purchased the land from the federal government during the first half of the 20th century. Hence, the land transferred from federal to state ownership.

The State Process, in brief, is an agreement that applies to Native American ancestral remains and associated funerary objects found on state or private lands in Colorado. The State Process is the result of a diverse workgroup, composed of the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs, state and federal government agencies, History Colorado, the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute Indian Tribes (the two Ute Tribes’ located in the state of Colorado), and forty-seven Tribes affiliated with the state of Colorado. Thirty-nine of the tribes issued letters of support, appointing the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute Indian Tribes as being responsible for culturally unidentified ancestral remains and associated funerary objects, which cannot be affiliated with a modern-day Indian tribe, and rebury them if they cannot be preserved in situ.

The Grand Junction Indian Boarding School students are considered culturally unidentifiable due to a lack of headstones or other primary documentation to identify the students’ graves. However, several non-destructive techniques can be used to assess the physiology of the human remains. Once the graves are located, forensic anthropologists can evaluate the ancestors’ teeth and specific skeletal regions to determine approximate age and sex. The information collected from these physiological methods, paired with Dr. Seebach’s archival data, will be disclosed and discussed with the consulting tribes throughout the duration of the State Process.

On Jan. 1, Dr. Seebach updated the NAGPRA Office about being approved by Dr. Holly Norton, Colorado state’s Archaeologist, to use a combination of techniques to assess two possible locations where the cemetery may lie on campus. Dr. Seebach and his team will first evaluate those locations using cadaver dogs, followed with the use of ground penetrating radar. Both techniques will be used to identify whether there are subsurface anomalies, such as the student cemetery. As the project progresses, the NAGPRA Office will keep tribal membership apprised through additional articles.

Please contact the Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s NAGPRA Office if you have any photos, information, or stories about those who attended the Grand Junction Indian Boarding School between 1886 and 1911. Managing the case on the behalf of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe are NAGPRA Coordinators, Cassandra Atencio and Garrett Briggs. Contact at catencio@southernute-nsn.gov/970-563-2989 or gbriggs@southernute-nsn.gov/970-563-2257.

This article submitted by Garrett Briggs | NAGPRA Coordinator Apprentice