Water Quality crew takes river health seriously

Though its methods have grown more technologically advanced, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe still keeps watch over local waters as it has for centuries.

After all, for all the comforts of civilization available today, the tribe and its members still largely rely on those waters for their livelihood. In the American West, where scarcity means water is as good as gold — especially during drought years, as have been the norm lately — ensuring the rivers and streams remain healthy is a top priority.

Enter the Southern Ute Water Quality Program. Part of Environmental Programs, a division of the tribe’s Justice & Regulatory Department, Water Quality is tasked with monitoring waters on the reservation for overall health — a complex balancing game that must take into account what’s right for local plant life and wildlife, including fish, but also for humans and the inevitable development that their presence brings.

To that end, senior water quality specialists Kirk Lashmett and Pete Nylander set off down the Animas River on catarafts June 18 and 19 — tens of thousands of dollars of specialized equipment and two Drum staffers in tow — to collect water samples that will be analyzed for a variety of factors.

Surrounded by recreational rafters bouncing around and off of rocks during the first leg of the trip — the crew entered the river at Memorial Park in northern Durango, on 29th Street — Lashmett and Nylander by contrast rowed swiftly, with a sense of purpose. Lashmett, a former professional raft guide who led the trip, seemed to know the river’s tributaries and inlets as one might know the veins on the back of their hand.

“Junction Creek is coming up,” he would say. And later: “Lightner Creek is just up ahead.”

At each confluence, the crew would pull ashore to measure both the tributary itself and the Animas some distance downstream, capturing the relative characteristics of each source and how they impact the health of the river as a whole.

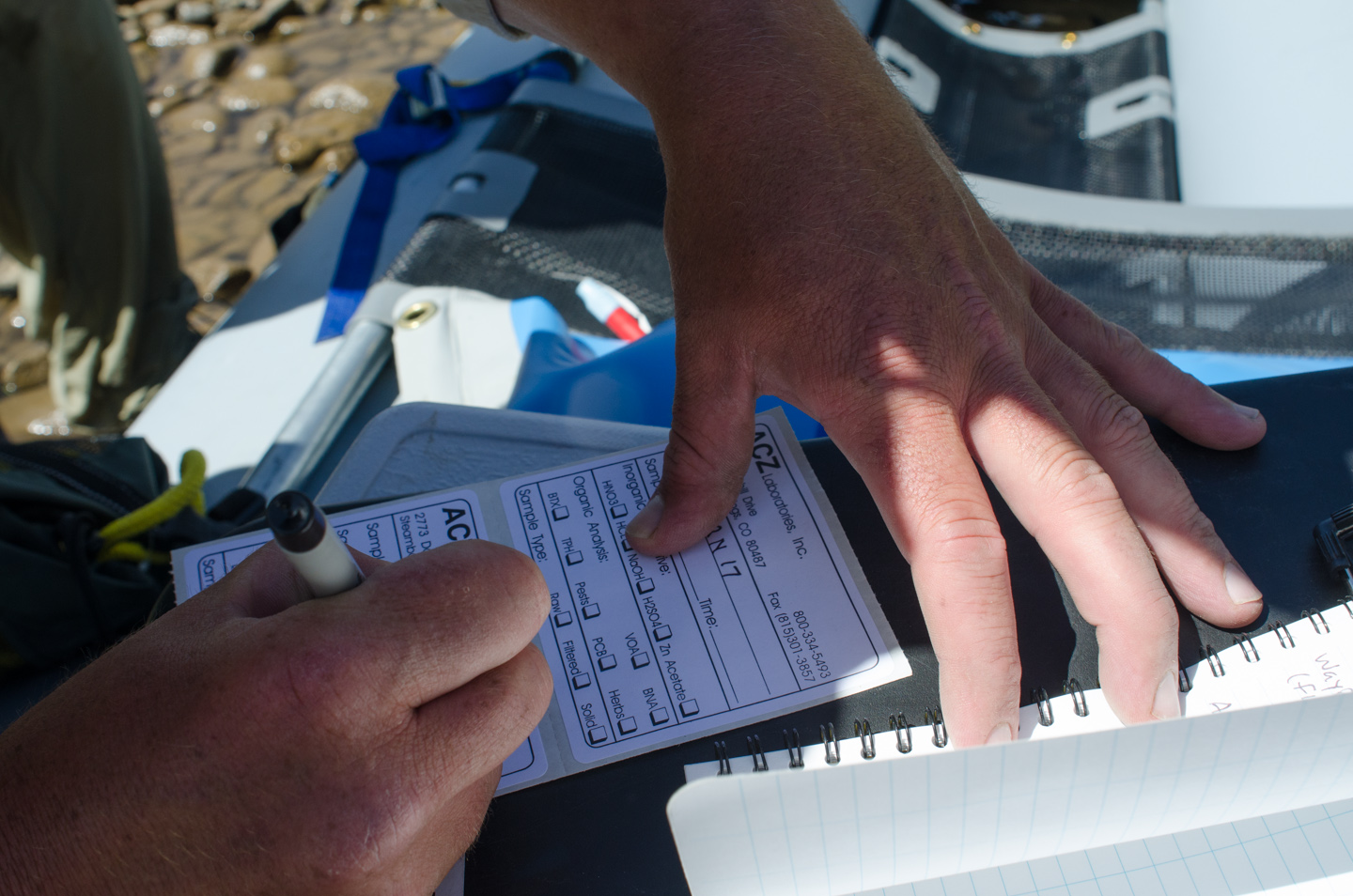

Measurements were taken in two parts. Lashmett, whose job is to monitor “point sources” of water pollution — those sources large enough to be differentiated from others, such as wastewater treatment plants and fish hatcheries — labeled and filled with water a pair of sample bottles. The bottles, one of which included sulfuric acid as a preservative and the other of which contained only a “raw” sample, are sent to a lab in Steamboat Springs, Colo., for analysis.

When results come back in a couple weeks, Lashmett said, they’ll include information about the levels of the nutrients phosphorus and nitrogen in the water. This is of particular concern to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, who awarded the tribe a grant in 2011 for such research.

While nutrients to a certain extent are obviously good, abnormally high levels can threaten aquatic life, Lashmett said. For example, they can lead to excess algae growth, affecting a cycle of high and low dissolved oxygen levels in the water that, at the extreme, can kill fish.

While Lashmett collected samples, Nylander produced a very expensive-looking (and indeed, very expensive) piece of equipment roughly the size and shape of a tennis ball canister called a sonde. Attached by a length of wire on one end to a display in Nylander’s hand, the sonde was carefully lowered into the water at each stop. Roughly 30 seconds later, the display would light up with a host of useful technical information — water temperature, salinity, turbidity (clarity), dissolved oxygen levels and more.

These measurements were stored in the device for import to a computer later, said Nylander, who oversees “non-point sources” of water pollution — those that are individually too small to isolate as contributors, such as agricultural fields and degraded stream banks and riparian areas.

Also housed in cages and chained to the riverbank in inconspicuous places along the Animas are five more sondes. These take measurements every half-hour even when staffers are not present. Lashmett said he likes to visit them every two weeks to download data. A sixth resides in the Pine River.

All this data collection helps the Water Quality Program paint a comprehensive picture of river health in the area, creating a foundation to inform future decisions on water issues.