For the last few years, Native friends have shared their Christmas plans and traditions with Smithsonian Voices. This extraordinary year, we asked how the Covid-19 pandemic is affecting people’s families and communities. The introduction of Christianity to the Americas can be controversial in Native circles. Europeans knowingly replaced Native people’s existing spiritual beliefs with the beliefs taught in the bible. Cruelty and brutality often accompanied this indoctrination. Yet it is also true that some tribes, families, and individuals embraced the bible and Jesus’ teachings. This complicated history is reflected here, as well.

These stories were compiled by Dennis W. Zotigh (Kiowa/San Juan Pueblo/Santee Dakota Indian), a member of the Kiowa Gourd Clan and San Juan Pueblo Winter Clan and a descendant of Sitting Bear and No Retreat, both principal war chiefs of the Kiowas. Dennis works as a writer and cultural specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

The introduction of Christianity to the original peoples of the Americas can be controversial in Native circles. Europeans brought Christianity to this half of the world and imposed it on Native communities, knowingly replacing existing spiritual beliefs with the beliefs taught in the Bible. Cruelty and brutality often accompanied the indoctrination of Native peoples. Yet it is also true that some tribes, families, and individuals accepted the Bible and Jesus’ teachings voluntarily.

Music played an important part in converting Native people, establishing their practice of worship, and teaching them how to celebrate the Christmas season. Perhaps the earliest North American Christmas carol was written in the Wyandot language of the Huron-Wendat people. Jesous Ahatonhia (“Jesus, He is born”) – popularly known as Noël huron or the Huron Carol – is said by oral tradition to have been written in 1643 by the Jesuit priest Jean de Brébeuf. The earliest known transcription was made in the Huron-Wendat settlement at Lorette, Quebec, in the 1700s.

During the 1920s, the Canadian choir director J. E. Middleton rewrote the carol in English, using images from the Eastern Woodlands to tell the Christmas story: A lodge of broken bark replaces the manger, the baby Jesus is wrapped in rabbit skin, hunters take the place of the shepherds, and chiefs bring gifts of fox and beaver furs. A much more accurate translation by the linguist John Steckley, an adopted member of the Huron-Wendat Nation of Loretteville, makes clear that the carol was written not only to teach early Catholic converts within the Huron Confederacy the story of Jesus’ birth, but also to explain its significance and to overturn earlier Native beliefs.

All throughout Indian Country, Native people have gathered in churches, missions, and temples to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ by singing carols and hymns in their Native languages. In some churches, the story of Jesus’ birth is recited in Native languages. Some Native churches host nativity plays using Native settings and actors to re-enact the birth of Jesus Christ. Among Catholics, Christmas Eve Mass traditionally begins in Indian communities at midnight and extends into the early hours of Christmas Day. In tipis, hogans, and houses, Native American Church members also hold Christmas services, ceremonies that begin on Christmas Eve and go on all night until Christmas morning.

In contemporary times, traditional powwow singing groups have rearranged Christmas songs to appeal to Native audiences. A humorous example is Warscout’s NDN 12 Days of Christmas, from their album Red Christmas. Native solo artists also perform Christmas classics in Native languages. Rhonda Head (Cree), for example, has recorded Oh Holy Night, and Jana Mashpee (Lumbee and Tuscarora) Winter Wonderland sung in Ojibwe.

Native communities host traditional tribal dances and powwows on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Among the Pueblo Indians of the Southwest special dances take place, such as buffalo, eagle, antelope, turtle, and harvest dances. The Eight Northern Pueblos perform Los Matachines – a special dance-drama mixing North African Moorish, Spanish, and Pueblo cultures – takes place on Christmas Eve, along with a pine-torch procession.

In an earlier year, Grandson Maheengun Atencio and Grandmother Edith Atencio prepared for the Matachines Christmas Eve dance at Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, New Mexico. Due to the pandemic, many ceremonial dances across Indian Country have been postponed, as Native people are very concerned for the safety of their elders.

For Native artisans, this is traditionally the busy season as they prepare special Christmas gift items. Artists and craftsmen and women across the country create beadwork, woodwork, jewelry, clothing, basketry, pottery, sculpture, paintings, leatherwork, and feather work for special Christmas sales and art markets that are open to the public. For the 15 years before 2020, the National Museum of the American Indian held its annual Native Art Market in New York and Washington a few weeks before Christmas. This year, the in-person event was replaced by an online program of interviews with artists from earlier Art Markets, Healing through Native Creativity.

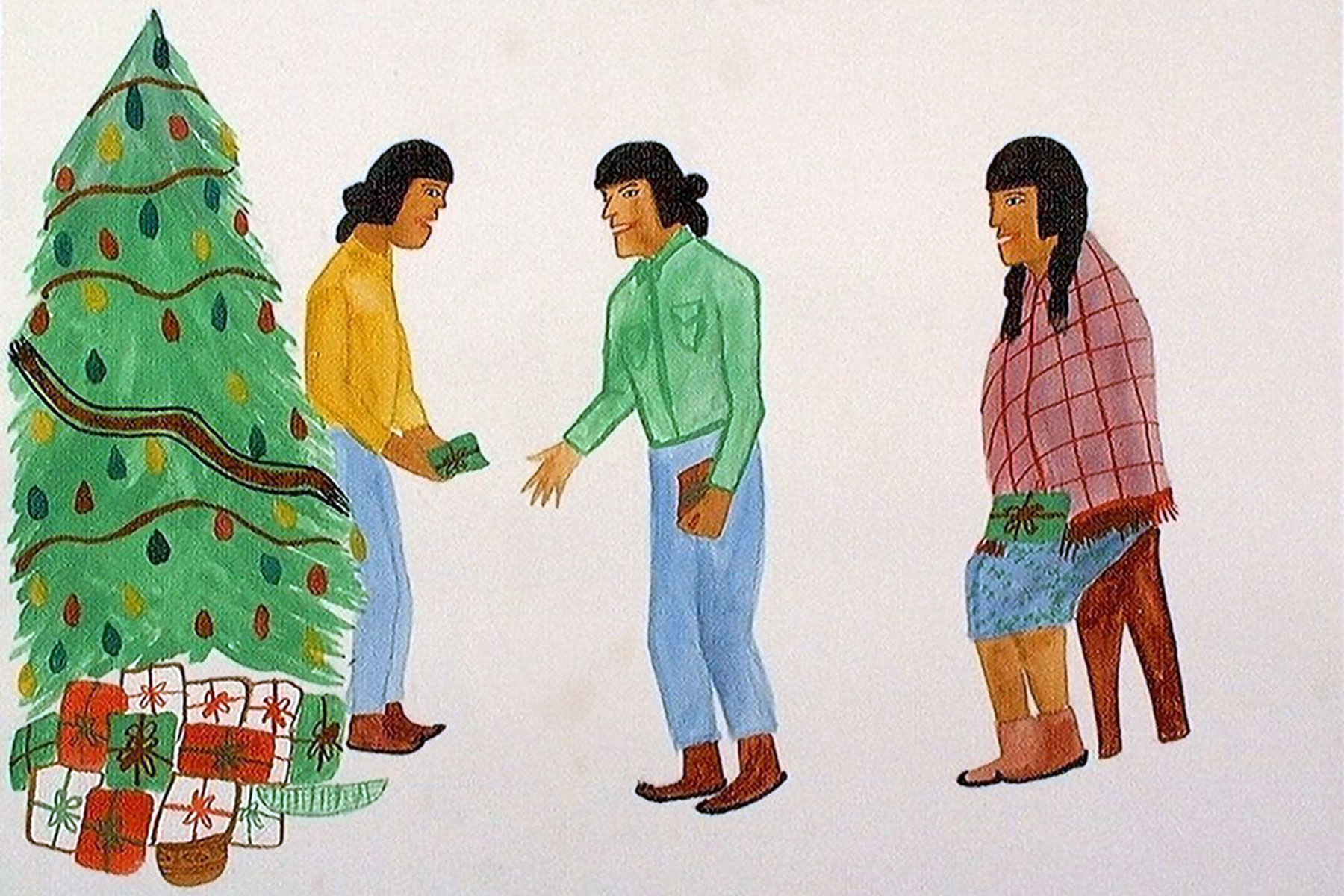

In many communities and homes, Christian customs are interwoven with Native culture as a means of expressing Christmas in a uniquely Native way. The importance of giving is a cultural tradition among most tribes. Even in times of famine and destitution, Native people have made sure their families, the old, and orphans were taken care of. This mindset prevails into the present. Gift-giving is appropriate whenever a tribal social or ceremonial gathering takes place.

In the same way, traditional Native foods are prepared for this special occasion. Salmon, walleye, shellfish, moose, venison, elk, mutton, geese, rabbit, wild rice, collards, squash, pine nuts, red and green chile stews, pueblo bread, piki bread, and bannock (fry bread) are just a few of the things that come to mind. Individual tribes and Indian organizations sponsor Christmas dinners for their elders and communities prior to Christmas. Tribal service groups and warrior societies visit retirement homes and shelters to provide meals for their tribesmen and women on Christmas Day.

According to the Urban Indian Health Commission, nearly seven out of every ten American Indians and Alaska Natives – 2.8 million people – live in or near cities, and that number is growing. During the Christmas holidays, many urban Natives travel back to their families, reservations, and communities to reconnect and reaffirm tribal bonds. They open presents and have big family meals like other American Christians.

For the last few years, Native friends have shared their families’ Christmas plans and traditions with the museum. This extraordinary year, we asked how the Covid-19 pandemic is affecting their families and communities. Thank you to everyone who took time to tell us a little about their lives.

Those replies are published on the Smithsonian VOICES website: www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-american-indian/2020/12/22/christmas-indian-country.