Arizona State University is a national leader when it comes to support, education and graduation for Indigenous students.

It was seeing herself reflected that made the college decision for Maria Walker.

The high school senior had been all set to go to Columbia University on a full scholarship, but then Tribal Nations Tour visited her school in the White Mountain Apache community. The outreach program brings Arizona State University students to schools throughout the state with large populations of American Indian students.

That spring 2017 visit made all the difference for Walker.

“It was heartwarming to see other Native Americans from ASU, who were successful and took the time to share their stories with us,” said Walker, now a senior in ASU’s College of Health Solutions. “It made me realize that if I went to ASU, I’d be studying with fellow Native Americans and be taught by Native staff who could help me along the way.

“I decided that I’d rather have a community at ASU rather than travel across the country and not know anyone or have the support I have now.”

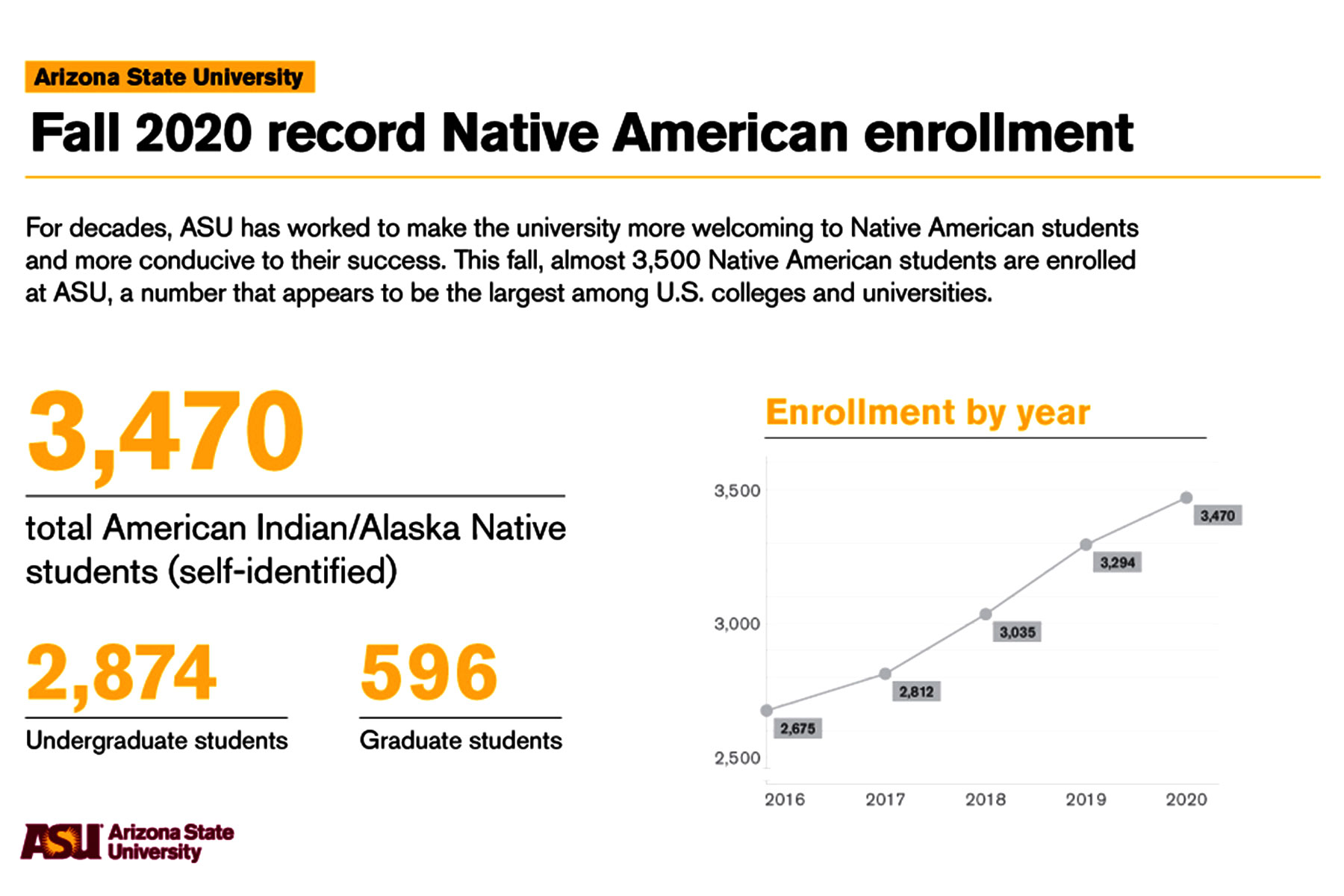

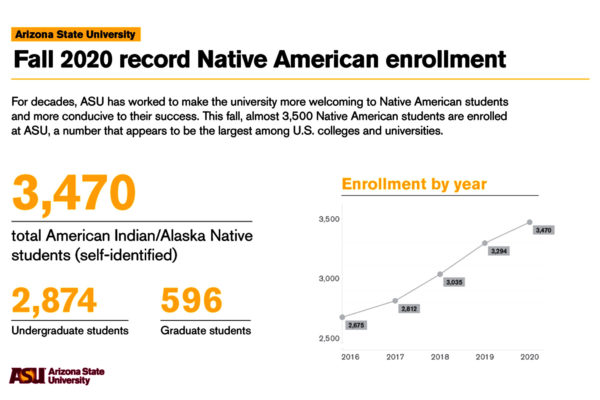

Walker is part of a growing number of Native American students at ASU, which reached almost 3,500* – 2,874 undergraduate and 596 graduate students – this fall. That number appears to be the largest among U.S. colleges and universities, according to ASU Now research. ASU is also one of the nation’s leaders in degrees granted to American Indian students on an annual basis; for the 2019-20 academic year, 663 Native American undergraduate and graduate students earned 679 degrees.

American Indian students make up less than 1% of all college students in the U.S., according to the National Center for Education Statistics, and only about 13% of all Native Americans have a college degree. Those numbers are starting to change, and ASU – whose Tempe campus sits on the ancestral homelands of many Indigenous peoples, including the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Xalychidom Piipaash (Maricopa) – is striving to do its part.

“There is so much potential here, and indeed, potential that is already being realized in very big ways,” ASU President Michael M. Crow said. “There is unbelievable energy to be found by asking, ‘Where is there opportunity to grow in understanding?’ ASU is making it a priority to serve Native American students, and in turn, these students are enriching the ASU community.”

Sixty years ago, when ASU opened the Center for Indian Education, the university had 17 Indigenous students enrolled at the university. Peterson Zah, the last chairman and the first president of the Navajo Nation and a consultant to ASU’s Office of Tribal Relations, first attended the university in 1959. He said getting to ASU was an adventure and an education in life.

Zah packed his luggage – a brown paper sack – placed his clothes and whatever possessions he owned in it, and hopped in the back of a pickup truck, commandeered by his uncle with his aunt riding shotgun.

“On the way down from the reservation, we stopped at a store in Payson to eat and gas up,” Zah said from his home in Window Rock, Arizona. “I could barely read or speak English, but I noticed a sign in the window that read, ‘Any good Indian is a dead Indian.’ I asked my uncle what that was about. He shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘People are just that way around here.’

“I asked him, ‘What am I going to school for?’” Zah said.

Soon he would find out – to help build capacity for his people and other tribes. In 1995, Zah was hired and tasked by then ASU President Lattie Coor to look for innovative ways to increase the number of American Indian students at ASU, which numbered 672 at the time.

Twenty-five years later, that number is far more substantial. And consider the COVID-19 pandemic has hit tribal communities particularly hard in 2020, it makes the milestone even more remarkable.

American Indian students have historically been driven by a sense of community and purpose, according to Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, President’s Professor, director of the Center for Indian Education and ASU’s senior adviser to the president on American Indian affairs. Native students often get a degree to pay it forward, by going back to their community and helping to strengthen and sustain it.

Students like Mariah Black Bird.

The 27-year-old is a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, and she is enrolled in ASU’s Indian Legal Program in the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

With financial burdens growing up, the death of her father when she was 14, and coming from an impoverished tribal community, Black Bird has had a lot of obstacles to overcome. But she knew education was her pathway to a brighter future.

“There were a lot of sacrifices that had to be made. I sold my car, worked summers and my mom let me borrow her car to come down to Phoenix,” said Black Bird, who is on an ASU scholarship, which she says covers about 75% of her costs. “Sometimes I don’t get to have a social life because I have to study, or I need to stick to a budget because things are tight. But I know it’s only temporary.

“I look at our history and know that even though we’re no longer battling it out at Wounded Knee or other famous sites, we’re still fighting. … I want to try to help my tribe any way I can, and our weapon of choice has to be education.”

In the not-so-distant past, an academic recruiting trip to a reservation in the state of Arizona was almost inconceivable. The trips were long and the reservations were hard to navigate, with populations spread out over wide spaces. The barriers were great.

That mindset changed about a decade ago, said Annabell Bowen, director of American Indian Initiatives for the Office of University Affairs. That’s when her team, with the help of Zah, created the Tribal Nations Tour outreach program. Each year, the tour holds presentations on wellness, college readiness, career preparation and the pursuit of academic degrees.

“ASU can’t be viewed as invisible, and we’re not waiting for students in tribal communities to come and visit us,” said Bowen, who schedules visits to all of Arizona’s tribes and has plans to visit other states such as California, New Mexico and South Dakota. “Through these visits, Indigenous youth are able to see themselves in our students and faculty.”

In addition to the Tribal Nations Tour, ASU has built a suite of programs to recruit, retain and build a sense of community for its Indigenous students. That’s important to Native American students and their families.

“Many times, when Indigenous students come to this university to visit our campus, they are accompanied by their families,” Brayboy said. “Nine times out of 10, the parents will say to us, ‘We are entrusting you to take care of our child.’ It’s a promise and responsibility we take seriously at the university.”

Beyond creating a welcoming environment, ASU realizes that connection is a worldview in how Native Americans are brought up, and that leaving the reservation is, in a way, a loss. Staff have worked hard over the years to present experiences of connection, belonging and shared identity.

The university has plans underway to redesign the campus to reflect Indigenous culture. Last year, the ASU Library announced its expansion of the Labriola National American Indian Data Center, which features thousands of books, journals, Native Nations newspapers and primary source materials, such as photographs, oral histories and manuscript collections. The Labriola Center now has two locations; Fletcher Library on the West campus and Hayden Library on the Tempe campus.

Future ideas include adding traditional Gila River pottery artwork to Sun Devil Stadium and building a storytelling pavilion and gathering place on campus. A “welcome wall” that includes the languages of the nearly two dozen tribes in Arizona was incorporated into the renovated Hayden Library.

Through these efforts, ASU is raising awareness of its Indigenous connection to all students, not just Native Americans.

*This number reflects students who self-identify as Native American. ASU’s enrollment according to IPEDS — the data program for the National Center for Education Statistics that is commonly used to compare institutions — is lower, because if a student identifies as both Hispanic and Native American, the Hispanic category takes precedence and the student is counted only as Hispanic.